Documentation-as-Code in Automotive System/Software Engineering#

Some days ago I stumbled over a PDF paper by Dr. Momcilo Krunic from 2023, in which he describes a docs-as-code implementation for an ASPICE-compliant SW development project at an Automotive supplier. And what can I say? This article by Dr. Momcilo Krunic is the best overview I have ever read, regarding the introduction of docs-as-code in a professional Automotive SW project. Therefore I decided to get in contact with him and ask for permission to republish his outstanding work in an HTML version so that single chapters are easier to link and share. It’s 100% in sync with the original post, I only needed to change 1-2 reference styles for technical reasons. And I added also some personal notes as dropdowns, pointing to extensions or slightly different implementation ideas.

Note

This post was written and published by Dr. Momcilo Krunic, as a paper for the Elektronika ir Elektrotechnika journal. The original version can be downloaded as PDF from ResearchGate. Original sources are available on a gitlab repository under Creative Common License 4.0. It’s also worth to visit his new startup: labsoft.ai.

Abstract

Documentation as Code (DaC) is an approach that applies the principles of software development to the production of technical documentation. By leveraging modern tools, DaC enables software engineers to treat documentation as a first-class citizen in the development process, alongside code and tests. In this paper, we discuss the advantages of DaC in system and software engineering, including improved accuracy, traceability, and maintainability. In the automotive industry, DaC has been used to document various aspects of vehicle development, such as requirements, design, testing, and compliance. This paper provides an overview of the state-of-the-art in DaC in the automotive industry and discusses the potential benefits and challenges of using this approach. Additionally, we present case studies and examples of how DaC has been used in the automotive industry to improve the quality and maintainability of documentation. This research has been conducted with more than 150 engineers contributing actively to DaC on the project for over a year within a company, so scalability of the presented solution has been tested. Finally, we provide a set of guidelines for teams to follow when adopting DaC to ensure successful implementation.

Introduction#

The automotive industry is facing increasing pressure to improve the quality and efficiency of software development for vehicles. One approach that has been gaining popularity in recent years is Documentation as Code (DaC), which treats documentation as a first-class citizen in the development process, alongside code and tests. The main idea behind DaC is to make documentation more accessible, maintainable, and up-to-date by storing it in the same repository as the code and using the same tools for version control, collaboration, and continuous delivery.

DaC has been applied in various domains, such as application development, IT, and web development. However, its application in the automotive industry is still in its infancy. The automotive industry has unique requirements and constraints, such as safety, cybersecurity, and compliance with standards like ASPICE [MH08] [asp], which make it challenging to apply DaC. Furthermore, the automotive industry has a long product lifecycle and requires maintaining documentation for a longer period.

This paper aims to provide an overview of the state of the art in DaC in the automotive industry and to discuss the potential benefits and challenges of using this approach. The paper will also present case studies and examples of how DaC has been used in the automotive industry to improve the quality and maintainability of documentation. The paper will be of interest to researchers, practitioners, and professionals in the automotive industry who are looking for ways to improve the quality and efficiency of software development for vehicles.

Also, this paper discusses the use of DaC in compliance with automotive standard ASPICE and the V-model. The ASPICE standard, which stands for Automotive SPICE (Software Process Improvement and Capability dEtermination), is a widely-used framework for evaluating and improving the quality of automotive software development processes. The V-model, on the other hand, is a widely-used software development model that describes the various phases of a project lifecycle and the relationships between them.

By integrating DaC practices into automotive system/software engineering, we can ensure that the documentation produced during the development process is accurate, consistent, and up-to-date. This can be achieved by using version control systems, such as Git, to manage the documentation, and by using automated tools to check the documentation for errors and inconsistencies. Additionally, by using the V-model, we can ensure that the documentation is produced in the appropriate phase of the project and is aligned with the requirements and design of the system.

The paper concludes that by using DaC practices in conjunction with the ASPICE standard and the V-model, we can improve the quality of automotive system/software engineering and ensure that the documentation produced is accurate, consistent, and up-to-date, as well as accessible and easy to use.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: The next section will provide a brief overview of DaC and its benefits. After that, the paper will present the processes and tools used in the case study, the research that inspired the writing of this paper, and examples of how DaC has been used in the automotive industry. Finally, the paper will conclude with a discussion of the potential benefits and challenges of using DaC in the automotive industry and future research directions.

Overview#

Documentation as Code (DaC) is a holistic approach to documenting technical information that can be applied to the development of technical documentation in Automotive engineering. By applying DaC, this research explores its ability to improve accuracy, traceability, maintainability, accessibility, and utilization.

The benefits of using DaC are considerable; it allows Automotive engineers to author technical documentation faster with more precision and less overhead cost. Automated processes such as automated builds or continuous integration pipelines can be used for creating documentation from source files and flowing changes into production systems quickly and reliably. Moreover, incorporating version control for tracking document changes helps Automotive engineers identify and address issues more quickly. Automated testing can also be used for validating the accuracy of documentation before it is released to production.

The art of documenting computer programs has evolved significantly over the past few years. Nowadays, many different tools and techniques are used to produce high-quality technical documentation. Some key trends and practices that are currently considered state-of-the-art in DaC include the following.

Use of Markdown and other lightweight markup languages: DaC often relies on storing documentation in plain text files that can be version controlled, reviewed, and rendered as HTML, PDF, or other formats. Markdown is a popular format for this purpose as it is easy to read and write, and can be converted to other formats using a variety of tools. Research presented in this paper used MyST (Markedly Structured Text) [mys] Markdown flavor as the language of choice for documenting technical information.

Automated documentation generation: DaC often uses tools and scripts to automatically generate documentation from code, comments, tests, and other sources, such as models or design artifacts. This helps to ensure that documentation is accurate and up-to-date with the code, and can reduce the effort required to maintain it. This case study utilized Sphinx [sphb] framework for automated documentation generation from code as part of the continuous delivery [HF10] process.

Use of version control systems: DaC relies on version control systems to manage and track changes to documentation, just like the code. This allows for collaboration, review, and rollback of changes, and enables traceability of documentation to specific versions of code. This is one of the key enablers of the DaC since it ensures that all software development artifacts are stored and released together. This simplifies forensics immensely since reproducibility is embedded in the system design. The research presented in this paper uses the Git version control system for managing all relevant artifacts: documentation, source code, tests, test results, and configuration files.

Use of model-driven development: DaC often uses model-driven development (MDD) approaches, where documentation is generated automatically from models of the system, and the documentation is kept in sync with the model, making it more accurate and up-to-date. In this research C4 architecture model [c4-] has been used to describe the system on various levels of abstraction: system Context, Containers, Components, and Code.

Adoption of DevOps practices to enable the process of continuous delivery [HF10]: DaC often follows the DevOps principles, which emphasize continuous integration and delivery, collaboration, and automation, which enables fast-feedback loops and transparency. This provides an opportunity to react as soon as the problem occurs, which makes it much cheaper and easier to resolve. More details about the DevOps tooling landscape used in this research are provided in the section “Processes and Tools.”

Processes and Tools#

To make the most of the DaC approach in the automotive industry, it is essential to have processes and tools in place that support its use. This includes process guidelines, source control systems, collaboration tools, and CI/CD servers, used for managing documentation alongside code and other artifacts. Automated methods should be employed for generating documentation from models of the system and validating various aspects of the generated documentation. Furthermore, traceability and consistency between requirements, design elements, source code, and tests is vital, hence, the need for a well-designed synergy between processes and tools. Automation ensures that documentation is accurate and up-to-date with changes in the system.

Processes#

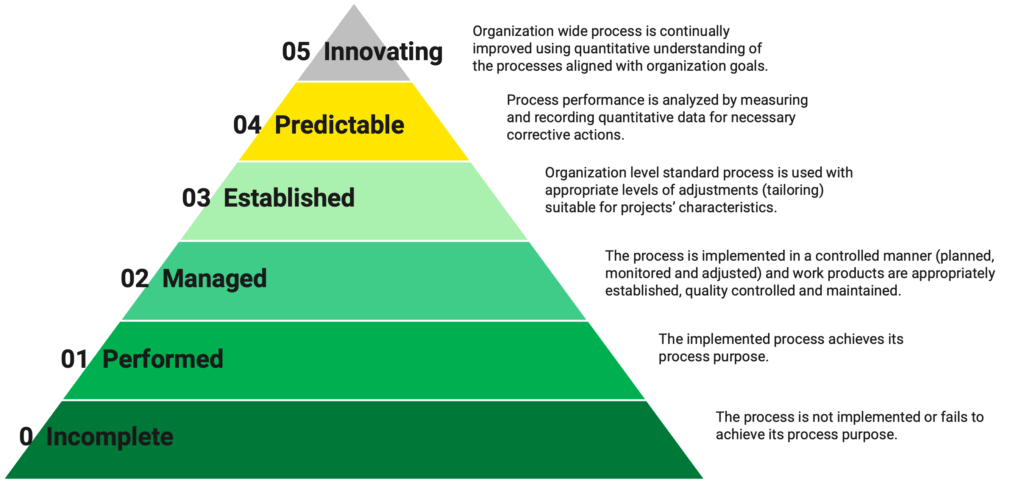

One of the conditions of the case study used in this research was the ASPICE (Automotive SPICE) standard Level 02 (Managed process) requirements (Fig. ASPICE process grading piramide). ASPICE (Automotive SPICE) is a process assessment model tailored to the automotive industry. It is based on the ISO 15504 (SPICE) standard and provides a structure to evaluate and enhance the software development process in the automotive industry. ASPICE is used in automobile system and software engineering to help automotive suppliers meet the expectations of Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEM). In this research, it has been utilized as the main process guideline/requirement for the implementation of DaC.

ASPICE process grading piramide#

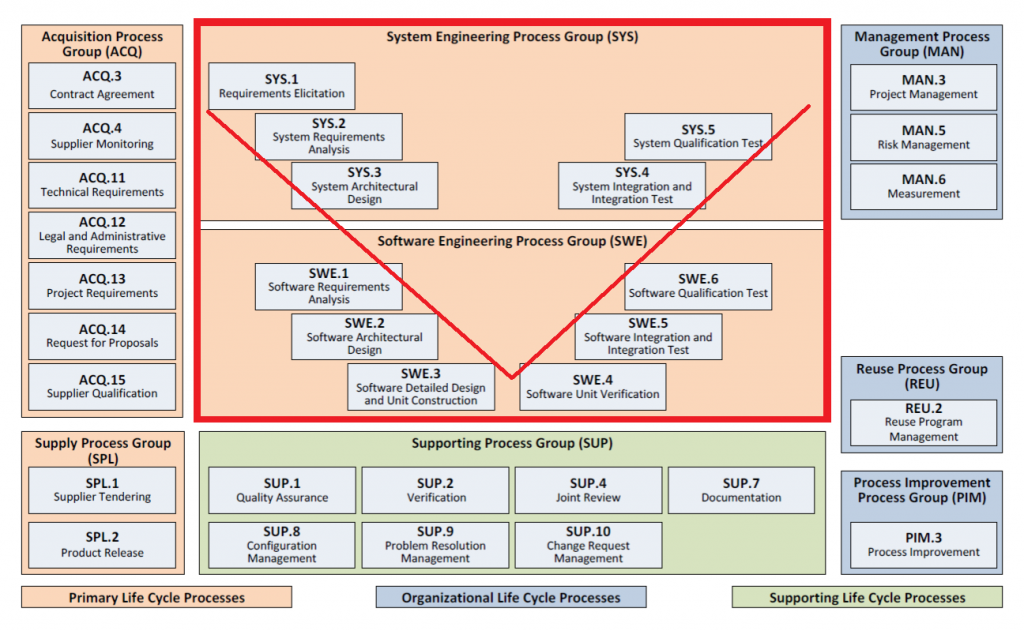

The ASPICE process model and the V-model are two widely used models in the automotive industry for software development. The V-model is a graphical representation of the development process, showing the relationships between different stages such as requirements, design, implementation, and testing. ASPICE provides recommended practices and guidelines to assess the current state of the software development process and identify areas for improvement. When used together (Fig. ASPICE V-model organization), these two models can help to ensure that software development is efficient, effective, and safe, thus improving the quality and safety of software development in the automotive industry.

ASPICE V-model organization#

It is essential to highlight that in this research, feature teams have been structured according to agile Scrum practices. As such, Sprint was the organizational cycle in which feature teams arranged their work. The regular process would assume that the Sprint planning feature team would agree with the customer about the scope for the following Sprint, using the System Architectural Design - SysAD (SYS.3) as a Project backlog. Then set of input requirements from the SysAD are decomposed into User Stories. User Story would be viewed as a software requirement to be consistent with ASPICE. Also, one User Story can be treated as an SWE Group V-model package (Fig. Jira as process guideline). What that implies practically is that User Story can not be considered finished before all SWE.1-6 artifacts are created or generated. To meet this quality requirement, and still be agile, feature teams tailored User Stories so they can be delivered in just one Sprint, by executing so-called micro-V cycles. This is the place DaC was a key empowering factor and without which this dynamic would not be possible, or it would be simply highly inefficient due to context switching. Treating documentation as code one can simply update what’s necessary, or create new content, without leaving the integrated development environment (IDE). These tasks should be considered alongside functionality when doing User Story tailoring and planning. Using micro-V cycles quality is embedded into the released software ground up, brick by brick (Sprint by Sprint), where User Story can not be merged into the main branch if the whole package (SWE.1-6) is not wrapped-up.

It is worth noting that the OEM defines SysAD, but the feature team can suggest modifications when they find a better design or demonstrate that the existing one is not feasible.

After going through several rounds of internal audits with the Quality Assurance Department, the DaC implementation used in this research, developed incrementally and iteratively executing micro-V cycles, was found to meet all the Base Practices set out for Software Engineering Group Level 2. This was a significant accomplishment, as it reassured management to adopt DaC practices across the organization.

Tools#

The DaC methodology involves using a range of tools to facilitate different stages of the software development process, including application lifecycle management (ALM) to track progress; documentation generation for accurate and up-to-date records; source control management to keep versions organized; CI/CD for automated delivery; and custom micro-tooling to streamline tasks. We used these tools alongside an existing tool (Windchill) to ensure backward compatibility with the exchange of requirements using the ReqIf format (Fig. Requirements exchange process between OEM and Tier 1 software supplier). This portion of the system requires improvement in both the process and the tools.

ALM alternative (note by Daniel)

In some of my projects, JIRA was just more as an issue system, caring about the implementation realization tasks, but not containing any technical requirements or specifications.

These were written down by the help of Sphinx-Needs, which allows a direct, continuous traceability between upper elements like system requirements and elements on the right side of the V-model, like integration test cases and their execution results.

As all of these elements were handled in one system, the complete traceability matrix could be easily graphically represented and also validated.

Requirements exchange process between OEM and Tier 1 software supplier#

As it can be seen from the (Fig. Requirements exchange process between OEM and Tier 1 software supplier) software development process starts once input requirements have been received from the customer in the ReqIF format, in the Windchill tool. This is part of the legacy process which is unfortunately still part of the software life-cycle management. The author of this study find this to be one of the hindrances to agile practices in the automotive industry, and it is something that needs to be changed to optimize the software development process and enable continuous delivery. In reality, this step is not followed strictly and the feature teams find alternate means of communicating directly with the customer and breaking down the problem, rather than passing the ReqIF back and forth. Direct communication with the customer should always be the preferred process, rather than a workaround.

In this study, Jira was employed as an Application Lifecycle Management (ALM) tool, but it was also used as a process guideline. Since the proposed system was designed to be team-focused, to reduce the context switching between different tools and environments, it was observed that the ALM tool could be used as a process framework as well. Entities of the ALM tool (Capabilities, Features, Epics, etc.) were used as placeholders for the process definition in the form of a Definition of Done (DoD). The DoD was versioned and stored on the Git repository together with other artifacts. When a feature team starts to work on a new Capability, it will clone the template and the entire structure illustrated in (Fig. Jira as process guideline), which serves a dual purpose: artifact life cycle management and process guideline/framework. It should be noted that Jira can be replaced by any other ALM tool, such as Redmine, Codebeamer, Polarion, etc. Moreover, it is important to recognize the clear relationship between the structure shown in (Fig. Jira as process guideline) and the SWE group in the ASPICE V-model (Fig. ASPICE V-model organization). This is an example of how the process and the tool can be combined to streamline the development process and increase the chances of consistently following the process.

Jira as process guideline#

Version control is a crucial component of the DaC system approach. For this research, Git was the obvious choice. It’s a state-of-the-art version control system and a reliable storage solution. This decision was made because Git had successfully met the needs of versioning and storing the only artifact that brings value to the customer - working software. This strategy simplifies the whole process of continuous delivery. When all artifacts related to the release process are stored and versioned in the same place, it becomes much easier to perform automated validations by the CI/CD server before delivering the software to customers, resulting in a better quality of the final product and higher customer satisfaction. Additionally, it is much easier to perform forensics when bugs are found. By simply checking out the released Git repository, all necessary information is available for an investigation into the particular release, including source code, test results, architecture, etc. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated in this research that adopting a trunk-based development approach [tru] is essential for the successful continuous delivery of both artifacts, working software, and documentation.

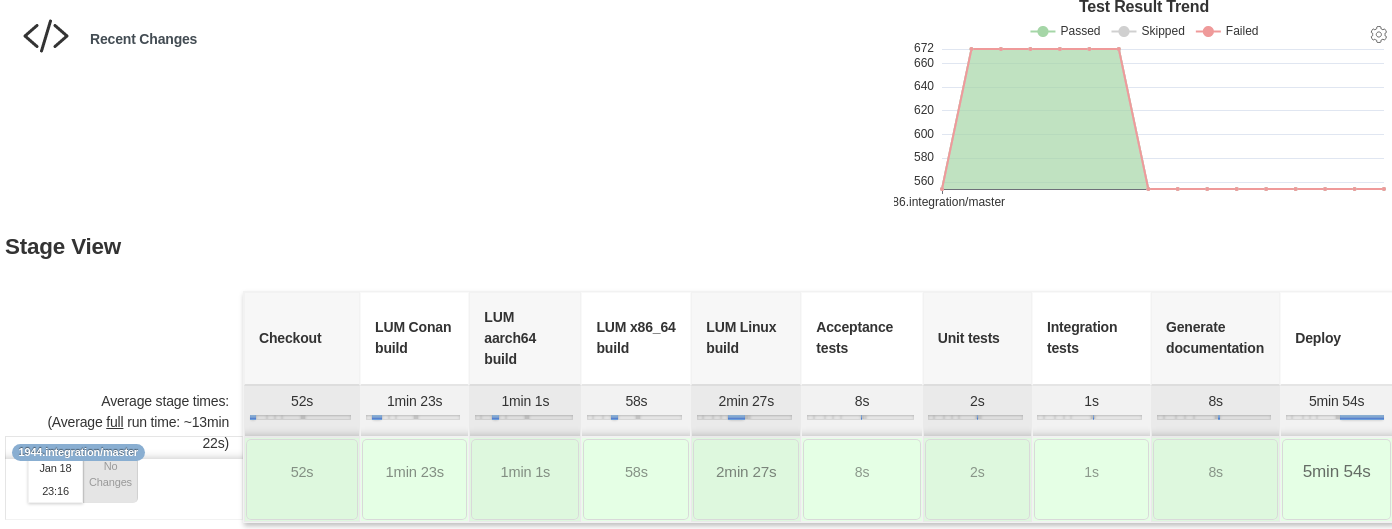

Continuous delivery [HF10] is a process that enables fast-feedback loops from customer to feature teams. This is essential for optimal steering of the software development process and discovering problems in the early stage. Next to the version control system, this CI/CD is the second most important component of the proposed DaC system. Automated builds were used to validate code and documentation, compile it and run tests. Automated deployments of documentation and software also took place. Automation of these processes is essential to avoid manual interventions and human errors. Automated builds, tests, and deployments are the core components of a continuous delivery pipeline, which can drastically improve the quality of software and documentation delivered to customers. In this research, Jenkins CI/CD build server has been used for both continuous delivery pipelines: Software (Fig. Continuous delivery pipeline for software) and documentation.

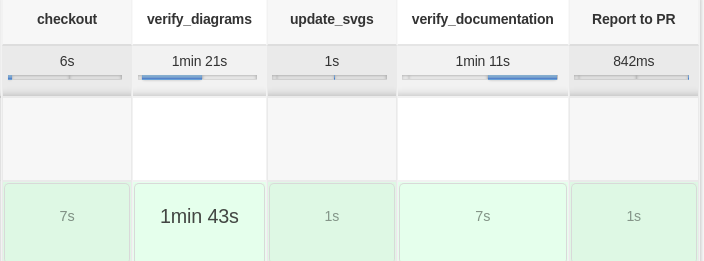

The continuous delivery pipeline for DaC has been divided into CI and CD pipelines to optimize the entire process. The Documentation CI (Fig. Documentation as Code Continuous Integration pipeline) pipeline is triggered on every Pull Request (PR) update. Its primary purpose is to keep all architectural diagrams up to date, as well as to serve as a quality gatekeeper and to prevent broken diagrams, links, etc. from being merged into the main branch.

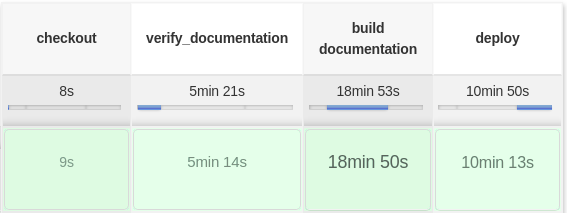

Whenever a PR is merged to the main branch, the Documentation CD (Fig. Documentation as Code Continuous Deployment pipeline) pipeline is launched. This pipeline carries out extra verifications, builds the documentation, and deploys the documentation as a static website to the designated documentation server.

The main reason for breaking DaC continuous delivery pipeline into two separate is execution time. DaC CI pipeline needs to be as fast as possible (execution time < 2min), as it serves as a gatekeeper to prevent PRs from being merged if something goes wrong. On the other DaC CD pipeline does not need to be as dynamic (execution time > 30min) since one can survive with outdated documentation for a half-hour.

Selecting a language for writing technical documentation is an important part of DaC system design. Markdown language [mar] was chosen for this case study for several reasons: it is lightweight and does not require any prior knowledge, it is portable across different operating systems and editors, it can be rendered directly on the Git repository (GitHub, GitLab, BitBucket, etc.), and it can be used with Sphinx [sphb] to create consistent and well-structured technical documentation from multiple Markdown files. Sphinx has been established as the tool of preference for fabricating technical documentation by many ventures [spha], such as one of the most noteworthy of all time, Linux [lin].

Documentation as Code - Case Study#

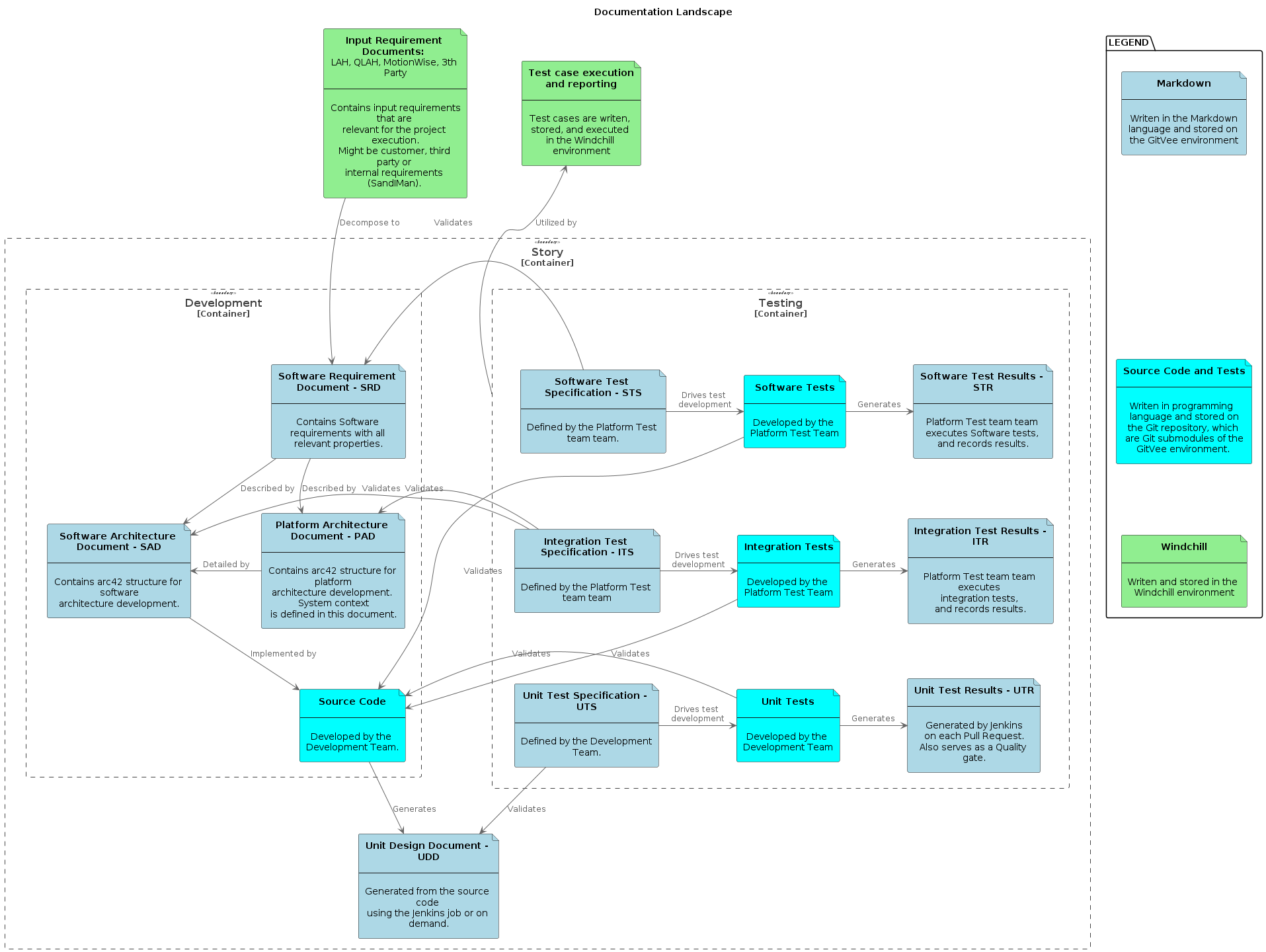

At the begging of this section let’s first identify all relevant documents (Fig. ASPICE SWE process group compliant documentation landscape) and map them to SWE process group (Fig. ASPICE V-model organization):

SWE.1 - Software Requirement Document (SRD)

SWE.2 - Software Architecture Document (SAD), Platform Architecture Document (PAD)

SWE.3 - Unit Design Document (UDD) - Generated

SWE.4 - Unit Test Specification (UTS), Unit Test Results (UTR) - Generated

SWE.5 - Integration Test Specification (ITS), Integration Test Results (ITR) - Generated

SWE.6 - Software Test Specification (STS), Software Test Results (STR) - Generated

ASPICE SWE process group compliant documentation landscape#

This research has been conducted during a joint effort between a software Tier 1 company and one of the largest German OEMs. During such collaborations, the usual practice is to have a Lastenheft and a Pflichtenheft. The first one, a Lastenheft, is a customer input requirement presented in the form of a SysAD (SYS.3 (Fig. ASPICE V-model organization)) or other documents. The second, a Pflichtenheft, represents the specification that describes in detail how the software Tier 1 will meet the customer’s requirements (Lastenheft). The actual implementation only begins after the customer has accepted the Pflichtenheft. In this context Pflichtenheft is directly connected with two layers (out of three) of the ASPICE Software engineering group, SWE.1 and SWE.2, consequently with three documents: SRD, PAD, and SAD. As one can notice these are the only three documents created manually from the entire documentation landscape (Fig. ASPICE SWE process group compliant documentation landscape). Also, it can be inferred that these three documents (SRD, PAD, and SAD) must always be up to date and consistent with the implementation, but also accessible by Tear 1 and OEM to communicate efficiently. For this purpose, it has enabled access to Pflichtenheft (SRD, PAD, and SAD) on the documentation server, through the VPN channel, so the customer can in real-time access these documents and discuss them with feature teams. This close feedback loop on the documentation level is important since it gives confidence to both tier 1 and customer about problem identification and some design choices. It is important to emphasize that a second feedback loop is established once working software is delivered to a production-like environment. Afterward, the next iteration loop can begin, Pflichtenheft is adjusted according to new learnings, and the source code is updated accordingly. Without DaC efficient dynamic of this iteration, the loop would not be feasible, and it would be much harder to keep the pace and consistency between upfront design, established in SRD, PAD, and SRD, and the implementation. This conclusion has been derived from the comparative analysis between the case study used in this research where DaC system approach has been widely adopted and other projects within the same company, where traditional exchange format between Tier 1 and OEM has been performed using ReqIF files (Fig. ASPICE V-model organization). This is one example where DaC systematic approach has an immense auspicious influence on the software development process dynamic, materialized through the fast feedback loop between the feature team and the customer. This enables incremental and iterative software development processes that usually lead to optimal solutions by any means.

The discipline required to keep consistency between software specifications, upfront design, and implementation can be difficult to maintain. Tools and processes that facilitate and motivate feature teams during software development to be diligent were the main drivers behind the research described in this paper. First, it is important to make documentation a habit. To do this, documentation should be attractive and easy to create [Cle18]. As feature teams are responsible for creating technical documentation and they like to do coding, then providing them an opportunity to “code” documentation felt like a natural choice. Also, the process of creating documentation can be done in the same integrated development environment (IDE), using the same tools. This reduces context switching (performance killer) and ineffective (extraneous) cognitive load.

There are three types of cognitive load [SMP19]: intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load. In terms of writing documentation, the intrinsic cognitive load could be knowing the syntax of the language to represent data. The extraneous cognitive load might be instructions to manage documentation files throughout the third-party document management system. Germane’s cognitive load is the only one related to intellectual activities that generate actual value, the documentation content. According to Cognitive load theory [SVMP98], one should “encourages learner activities that optimize intellectual performance”. Thus, DaC system approach has been designed as a function that minimizes intrinsic and extraneous working memory footprint and amplifies Germane cognitive load.

Intrinsic cognitive load has been minimized by selecting simple Markdown language as a choice for writing documentation. It is something closest to plain text, therefore it does not require almost any mental effort to express yourself.

Extraneous cognitive load has been decreased by: providing feature teams an opportunity to work on technical documentation without leaving the familiar working environment (IDE); reviewing, storing, and versioning the documentation next to the source code (on the Git repository); automating documentation verification, build, and deployment;

Germane cognitive load refers to the effort needed to create a lasting store of information. In DaC context, it is related to creating documentation that fulfills its purpose and brings value to the users: feature teams, customers, etc. Documentation can bring some value only if it is consistent with the source code. Reviewing, storing, and versioning documentation with the source code (and other relevant artifacts) it increases the chances for consistency, thus maximizing the value produced by engaged germane cognitive load.

Cognitive load can be also directly connected with accidental and essential complexity [Bro87]. Accidental complexity could be processes and third-party tools introduced to “facilitate” documentation management, but instead creates unnecessary extraneous cognitive load, thus it should be removed. Essential complexity might be the process of creating consistent usable content through the engagement of germane cognitive load.

Besides making a software development-centric documentation creation environment that motivates feature teams to write better documentation more often, there should be also some sort of gating mechanism and protection against undesired behavior, like introducing broken links, inconsistencies, etc. One important concept that helps to detect inconsistencies between implementation and documentation is traceability.

This research highlighted the important concept of traceability, which was explored and established through multiple levels and perspectives. The DaC system was of particular interest to the ASPICE auditors, prompting a careful design of its components. The first perspective of traceability has been established through the use of the ALM tool, which clusters related artifacts into a package called User Story. A single input requirement can be decomposed into multiple User Stories that can be interlinked and even share some development content, but each Story contains all the related artifacts necessary to deliver the Story in the form of a micro-V model increment. Another aspect of traceability is established through the branching strategy process. Although trunk-based development is promoted as the overall branching strategy, short-lived branches are allowed. The strategy is simple: when one starts to work on a particular subtask (SRD, SAD, etc.), it creates a branch. Since one Story should be completed within a two-week cycle (a Sprint), branches should not have a lifespan longer than that (ideally no more than a couple of days). It was also instructed to merge at least once a day to avoid merge conflicts and integration problems. This aspect of traceability is important for top-down analysis, as one can easily trace related work in the form of a branch by following User Stories and decomposed micro-V model subtasks. Each subtask should contain the link to the branch and related Pull Request where the review process happened.

Another perspective of traceability has been accomplished more in the DaC spirit through the source code (software and documentation). The idea behind this concept was simple: one should leave a piece of evidence in the source code (software and documentation) in the form of a User Story ID (generated by the ALM tool) wherever some work related to that Story occurred: decomposition in the (SRD), architectural design (SAD), writing implementation (source code), tests, etc. This is convenient from a development perspective since one can simply search for the Story ID in the IDE and all related micro-V model artifacts (SRD, SAD, source code, tests, etc.) will appear. If necessary those can be changed, and afterward, Pull Request should be created where the review process is initiated. This is also convenient for the official ASPICE audit process since it is straightforward to find all evidence by searching through the Git repository.

From the user’s point of view, one can do top-down traceability analysis using the ALM tool or bottom-up by searching for the Story ID in the Git repository. Furthermore, an automated gating system could be integrated into the PR handler to prevent merging the User Story into the main branch if artifacts from the micro-V model are missing, thus ensuring the releasable state of the main branch is maintained at all times. At the time of this research, the automated gating system was still under development, so the review process was the only way to prevent this behavior. The traceability graph builder was developed as a prerequisite for this automation, so the next step would be to integrate the gating system into the PR handler.

This research was motivated by the fact that software development is a relatively new engineering discipline (especially in the automotive industry) and there are many conflicting views about the proper software development processes. From conventional automotive waterfall processes, which heavily emphasize upfront design, to agile development techniques that question the need for documentation and prior design. The DaC system design, described in this paper, attempts to close this gap by providing some useful recommendations, so feature teams can promote technical excellence through lean software development practices and comply with automotive standards.

Requirements as Code - Executable Specifications#

Historically, in the automotive industry, requirements elicitation has been a continual process of clarifying the scope of the work that needs to be done between the customer and Tear 1 software supplier (Fig. Requirements elicitation process between Tier 1 and OEM). In practice, this usually means that the “customer collaboration over contract negotiation” agile principle is neglected, and the “contract game” happens by throwing Requirement Interchange Format (ReqIF) files over the fence.

The author of this research found this process relic of the past and something that needs to be replaced with direct collaboration between customer and feature teams. Writing good software requirements was never an easy task to do. This research adopted some practices proposed by the Behaviour-driven development (BDD) methodology to explore alternatives to the traditional approach and improve the process of defining the problem that needs to be resolved.

Behavior-driven development (BDD) is a software development methodology that emphasizes the collaboration between developers, testers, and stakeholders to define and understand the behavior of a system. It is an extension of test-driven development (TDD) and emphasizes the use of natural language and examples to describe the desired behavior of the system.

BDD uses a specific syntax called Gherkin to describe the behavior of a system in terms of User Stories and related scenarios (executable specifications), which are specific examples of how the system should behave in a certain context. These scenarios are written in a natural language format, making it easier for stakeholders to understand and provide feedback.

The process of BDD starts with the stakeholders defining the acceptance criteria/test [FP09] for the system in the form of scenarios (SWE.1 (Fig. ASPICE V-model organization)). These scenarios are then used as a basis for writing automated tests (SWE.6 (Fig. ASPICE V-model organization)), which are used to ensure that the system behaves as expected. The developers then implement the system and run the automated tests to ensure that the system behaves as described by the scenarios.

BDD is often used in conjunction with agile development methodologies, such as Scrum, and emphasizes the importance of continuous testing and feedback to improve the quality of the system.

Overall, BDD is a methodology that helps to ensure that the system is developed to meet the needs of the stakeholders by fostering collaboration between the different roles involved in the development process and providing a clear and common understanding of the system’s behavior.

In this research, feature teams have used SRD template [srd] for the decomposition of input requirements (SYS.3 (Fig. ASPICE V-model organization)) into User Stories and scenarios. SRD is then stored and versioned on the Git repository, next to the source code, software architecture, and other relevant artifacts. This is important to emphasize because, with this file organization, it is easy to change User Stories and scenarios from the same IDE, and perform baselining with the same tool (Git) for the whole micro-V model package. This setup enables incremental and iterative modus operandi between feature teams and customers.

Requirements elicitation process between Tier 1 and OEM#

Architecture as Code#

One of the major challenges during system (software) design is managing complexity. This has an immense influence on the maintainability of the system since complexity is what makes software hard to change. Major complexity inceptions are irreversible design decisions and all workarounds that come after. To avoid this, and reduce accidental complexity, creating software architecture for such a complex system should be an iterative process [Far21] with close collaboration with various stakeholders. The most important quality attribute of the software architecture becomes how easily it can be changed.

“First make the change easy (warning: this might be hard), then make the easy change.”, Kent Beck

In modern software development practices, creating software architecture is a continual collaborative process between various stakeholders. Conway’s law [Con68] teaches us that organizational team structure represents a blueprint when it comes to crafting system (software) architecture and that organizations that recognize this have more chances to succeed [SMP19]. When creating a new system, organizations can apply inverse Conway’s law maneuver, and organize teams in the such constellation to achieve desired system architecture. As one can notice management of the company becomes a system architect, or at least an influencer, through the creation of teams organization. This becomes inevitably a big upfront design that is so loathed by the agile community. Communication between management and feature teams becomes imperative to create an optimal system design, therefore “there is no silver bullet” solution when it comes to crafting such design.

There were many attempts in the past to create no code, drag and drop, and graphical environments for crafting system/software architecture. The problem is not to create a such graphical environment that can enable non-technical people to drag and drop software elements, make some connections, and then generate some code out of it. The problem is the maintenance of the such product (system/software architecture). How to establish efficient and sustainable round-trip between these graphical design elements and the source code. When design changes, how to integrate generated source code with the existing code base. When the code base is changed, how and when to update the graphical representation. Many organizations abandoned the first part (to generate code out of graphical elements), but kept only the second, to regularly update the graphical representation of the code base to ensure consistency. Similarly like for the rest of the documentation the main enabler for keeping consistency between architectural design and the source code was to make it attractive and easy to change to become a regular habit [Cle18], as well as to make it functional and integral part of the software development cycle.

The role of a software architect has evolved from being the mastermind of system design to being a feature team facilitator and teacher. Now, crafting software architecture is a whole team activity. To make architectural work more engaging for software developers, the obvious choice is to make it more coding-like. The same conclusion applies when it comes to making architecture easy to change, operational, and functional vise. Software engineers like to develop software, so providing them an opportunity to craft architecture in the same manner and using the same working environment, increases the chances that the team will treat it equally to source code and keep it consistent. Text is the most powerful abstraction. There were many attempts in the past to create an architectural language like ADL, ArchiMate, ABACUS, etc. In the automotive community Genivi foundation defined Franca as Interface Definition Language (IDL) and Franca+ as an extension that enabled a language-based modeling approach for AUTOSAR environments [SBS20]. The main advantage of this approach is that it provides a mechanism to automate source code generation from the model using the CI infrastructure and thus ensuring consistency between the model, source code, and configuration files all the time. A similar approach has been taken in this research, where it has been developed in-house domain-specific language (DSL) based on textX framework for modeling AUTOSAR environment on the code level (Level 4 [c4-]).

Besides generating the source code from the model, software architecture’s main purpose is to tell the story of the software [c4-]. This is important because it exposes the internal structure (static architecture) and behavior (dynamic architecture) of the system and prevents inceptions of accidental complexity to crawl into the design and make software architecture more difficult to change. In this research C4 model [c4-] has been used for presenting architecture on four levels of abstraction: System Context, Containers, Components, and Code. As it has been mentioned, the Code level has been modeled using custom DSL to generate AUTOSAR arxml model and source code. Three other levels have been modeled using the PlantUML [plaa] language and C4 model extension [plab] (the same language that was used in this paper for creating figures). During this research, PlantUML files were stored and versioned on the Git repository next to the source code and other artifacts. The output of the PlantUML are svg images that are referenced in the Software Architecture Document (SAD). These images are updated by the CI process (Fig. Documentation as Code Continuous Integration pipeline) on every Pull Request. Also, one interesting feature of the PlantUML language is that its support includes preprocessing directives, which enables the reusability of PlantUML elements and the creation of composite diagrams. Quality Gate CI pipeline (Fig. Documentation as Code Continuous Integration pipeline) ensures that one can not merge broken diagrams into the main branch.

In this research arc42 [arc] SAD template [sad] has been used for documenting software architecture. The fifth part of the SAD, known as the “Building Block View”, is where the C4 model should be described in detail.

Unit Detail Design as Code#

Test Driven Development (TDD) [Bec03] is an effective software development process that serves primarily as a design technique. It helps to create code that is reliable and easy to change (maintain). The TDD process involves writing tests before coding so that one can be sure the code works as expected. The usual TDD cycle includes the following:

Writing test that fails - RED

Writing implementation that makes the test pass - GREEN

Removing duplications and increasing quality - REFACTOR

Writing the test first has an immense impact on the quality of the source code design. Implementation created this way is written having testability in mind. TDD represents the most powerful mechanism to manage main software quality properties such as modularity, cohesion, separation of concerns, abstraction, and managing coupling [Far21]. This mechanism is established through an instant feedback loop in form of writing tests. If it becomes too hard to write the test for a certain peace of functionality, due to many different reasons, like the setup is too complex, etc., it might be a good point in time to revisit the design. This instant feedback helps in managing the complexity of the system that is being built. Also, it gives confidence to the feature team to perform source code refactoring more often.

The tests for our software should be understandable, maintainable, repeatable, atomic, necessary, granular, and fast. They should be focused on the behavior of the system rather than a specific implementation and should be easy to change while remaining true to the system. They should be deterministic and provide the same result every time they run. Tests should be isolated and focus on a single outcome and must be necessary to guide our development choices. They should be small, simple, and focused, and provide a clear pass/fail result without needing interpretation. Lastly, they should be fast to serve as a tool to guide our development.

When the feature team utilizes TDD as a routine and writes tests according to the guidelines written above, then those tests become Unit Detail Design (SWE.3 Fig. ASPICE V-model organization) and validation (SWE.4 Fig. ASPICE V-model organization). In this research, not all teams have followed TDD practices, but those who did, used tests produced this way for SWE.3 and SWE.4. Tests have been stored and versioned on the Git repository next to the source code that validates.

Testing, Validation, and Verification#

Testing, validation, and verification are usually connected with the right side of the V-model (Fig. ASPICE V-model organization). In this research micro-V iterative loops have been executed throughout regular development cycles daily, including the right side (Fig. Continuous delivery pipeline for software). Two different contexts of testing, validation, and verification were performed during this research, both automated as part of the CI loop. Testing, validation, and verification of the software that is developed (Fig. Continuous delivery pipeline for software) and of technical documentation that is being produced along the way (Fig. Documentation as Code Continuous Integration pipeline).

During this research, testing of the software has been performed on three levels (Fig. ASPICE V-model organization):

SWE.6 Software Qualification tests - Acceptance tests (executable specifications) are developed as part of the BDD process of defining acceptance scenarios using Gherkin syntax (for each User Story), before any development activity. These tests (executable specifications) validate the expected behavior of the software on the highest level of abstraction. There is no need for additional tests on this level. The direct advantage of Requirements as Code approach.

SWE.5 Integration tests - Generated from the DSL architectural model, using the integration test framework developed for that purpose. This has been enabled by treating Architecture as Code. These tests verify that the specification of the architecture model is met (interconnections between software components), therefore ensuring consistency between software architecture and implementation.

SWE.4 Unit Validation tests - Developed through practicing TDD, before implementation, following the red, green, and refactor cycle. These tests validate the behavior of software units on the lowest level of abstraction. No need for extra test development in addition to this, which is a direct consequence of Unit Detail Design as Code approach and following TDD methodology.

This CI/CD pipeline (Fig. Documentation as Code Continuous Integration pipeline) is triggered on every PR update. Upon the completion of each execution, test results at all three levels are documented in the Jenkins job and uploaded to the Git repository, thereby creating a historical record and ensuring transparency at all times. PRs that do not pass all stages in the CI/CD pipeline (Fig. Documentation as Code Continuous Integration pipeline), are marked as unapproved by the system-builder and can not be merged to the main branch before being fixed, thus establishing a direct feedback loop towards the PR author.

Continuous delivery pipeline for software#

Establishing and maintaining consistent technical documentation is a difficult task, thus necessitating the implementation of systematic remedies to ensure its successful realization. In the case of the DaC approach, the validation and verification of documentation are conferred to CI (Fig. Documentation as Code Continuous Integration pipeline) and CD (Fig. Documentation as Code Continuous Deployment pipeline) pipelines.

Documentation as Code Continuous Integration pipeline#

To ensure consistency of PlantUML files and software architecture, on each PR all diagrams are regenerated, and updated svg files are automatically pushed to the Git repository. Consequently, all references to architectural diagrams (svgs) in the documentation are updated thus keeping SAD up to date. Tedious and error-prone manual processes of generating svgs have been delegated to the CI pipeline thus offloading feature teams of such activity and making more room for engagement of germane cognitive load. To optimize CI pipeline (Fig. Documentation as Code Continuous Integration pipeline) execution time, only modified Markdown files from the PR which triggered the pipeline execution is verified. If all stages pass, PR is approved by the system-builder, otherwise, it is marked as unapproved, and can not be merged into the main branch, until the pipeline is green.

CD pipeline (Fig. Documentation as Code Continuous Deployment pipeline) is triggered by the merge to the main branch. It performs additional checks on the whole documentation landscape, not just files modified by the PR. If this stage pass, documentation is built with the Sphinx [sphb] and deployed to a dedicated documentation server. It might happen that some changes have been merged to the main branch before the issue has been discovered on the documentation deployment pipeline. That will prevent deployment of the latest changes, but still keep documentation in a consistent state, slightly outdated but consistent. PR creators will be notified automatically to fix the issue. Taking into consideration the dynamic of merging changes multiple times per day (and fixing such issues), it has been decided this trade-off is acceptable. It is much more important to establish fast feedback loop on the CI pipeline, rather than to be bulletproof. Issues that are missed by the CI are caught by the CD pipeline. The study has shown that those issues rarely occur, and establishing a fast feedback loop on the PR is of utmost necessity.

Documentation as Code Continuous Deployment pipeline#

Results and Discussion#

Stability and Throughput are the only two measures that could be used to evaluate changes applied to processes, tools, technology, etc.[FHK18] [Far21]. When we change a process (or whatever) we can measure the impact of this change on either of these two measures and steer changes accordingly.

Stability was tracked during the research as one of the key metrics, measured by the number of reported defects. The results revealed interesting findings. The blue bars depicted in (Fig. Measured stability throughout the first year of the Project) represent the reported defects during the research in 2022 when the DaC approach was applied, while the red bars represent the number of reported defects in the legacy project in 2020. To make the comparison more meaningful, data was collected during the same phase of the projects and the customer was not changed. The same feature teams were mostly involved in both projects, with the only difference being the software development methodology. In the project where the DaC approach was applied, 35% fewer defects were reported on average than in the project where legacy processes and tools were utilized. This number is quite similar and comparable to the results from different studies [WMV03] [MJ07], where the impact of the test-first approach (TDD) on defect reduction ranged from 40%. In another study [FHK18], it was measured that feature teams that employed techniques like those presented in this paper (BDD, TDD, Continuous Delivery, etc.) spent 44% more time performing useful tasks.

Measured stability throughout the first year of the Project#

In addition to the reported defects, (Fig. Measured stability throughout the first year of the Project) shows additional useful data on the Throughput and the effects of continuous and disruptive delivery processes on reported defects. It’s important to note that this was one of the main philosophical/process-based differences between the two projects observed in the case study. Throughput in the DaC Project was managed through continuous delivery, whilst in the Legacy Project it was disruptive. The three red peaks on the (Fig. Measured stability throughout the first year of the Project) indicate the number of reported defects just after disruptive delivery occurred. In the case of the DaC Project, (Fig. Measured stability throughout the first year of the Project) shows a linear progression in the number of reported defects. This is expected due to the continuous delivery process, and the fact that the number of delivered lines of code (LOC) increased over time, but the ratio [defect]/[LOC] remained constant.

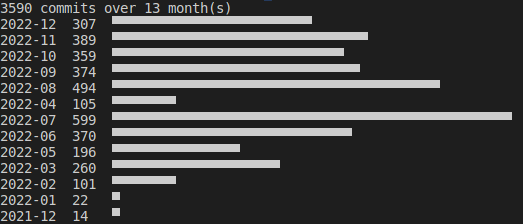

Documentation repository statistics (commits per month)#

The interesting statistic can be derived from the documentation repository (Fig. Documentation repository statistics (commits per month)). The statistic provides data about the number of commits per month related to the DaC approach during the research. In the first couple of months, the whole infrastructure was created and feature teams were onboarded. Afterward, there was a steady influx of commits per month related to the creation of technical documentation (executable specifications, architecture, unit design, etc.). When comparing this statistic to the almost non-existent documentation from the Legacy project, a direct correlation can be made between treating documentation as a first-class citizen (DaC) (Fig. Documentation repository statistics (commits per month)) and a reduced number of reported defects (Fig. Measured stability throughout the first year of the Project).

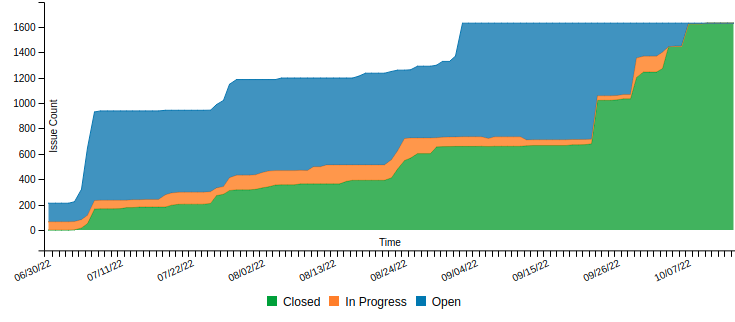

Release cumulative flow chart#

The cumulative flow diagram in (Fig. Release cumulative flow chart) shows a snapshot of Throughput during the research. It indicates that 1629 subtasks related to the micro-V model (Fig. Jira as process guideline) (Story[container]) were completed within three months. Notably, 184 User Stories were delivered across five different features over the same period, averaging six Stories per Sprint. This high pace was made possible by tailoring the User Stories to include both implementation and documentation.

The DaC approach has enabled a high-paced Throughput, by providing feature teams an opportunity to work on all micro-V model artifacts in a single working environment for software and documentation development. In DaC approach, documentation is treated equally as important to source code and delivered together, whereas in other (legacy) projects it was usually done at the end of the project life-cycle. This has a significant negative impact on the quality of the delivered software ((Fig. Measured stability throughout the first year of the Project)), since if documentation is treated separately from implementation, it usually means that design decisions were taken ad hoc and not communicated properly to other stakeholders. This can lead to suboptimal system architecture that is difficult to change, negatively impacting the maintainability of the system and other quality attributes.

When comparing state-of-the-art automotive software development practices and our approach that introduces DaC, in terms of quality and efficiency of a delivered product, there are several points to consider:

Process improvement: ASPICE provides a process framework, a set of recommended practices and guidelines for software development, testing, maintenance, etc. to improve the efficiency of the software development process. It emphasizes that processes should fulfill their purpose, make sense, and bring value to the user. The DaC approach brings process improvement by removing waste embodied in processes and third-party tools overhead, reducing context switching significantly, and improving performance. The working environment and processes have been designed to be software development-centric, adjusted to the only stakeholders in the entire system that generate actual value for the customer. This has an auspicious impact on the quality since feature teams are treating documentation as code and keeping it consistent with implementation. Up-front design (Architecture as Code) and testability of the system (executable specifications, and UDD as code), became highly integrated and important software development properties in the DaC approach.

Collaboration improvement: The DaC focuses on improving collaboration and accessibility of the documentation to all relevant stakeholders, as well as facilitating inter- and intra-team communication. By treating DaC, developers can work on the documentation in parallel with the codebase, which increases the efficiency of the development process. All important design decisions are communicated through the regular Pull Requests review process (intra-team), leaving a historical record as evidence of evolutionary design. When it comes to cross-cutting decisions affecting multiple domains (feature teams), the DaC approach resolves this systematically by utilizing the Git Codeownership mechanism. Improved collaboration and communication prevent accidental complexity to creep into the design making architecture more flexible.

Traceability: The DaC approach allows for better traceability of the documentation, as it is stored in version control systems and can be easily linked to the codebase. All micro-V model artifacts are traceable from different perspectives. Most importantly, software developers can search for a Story ID and find all relevant micro-V model artifacts in the working environment, making it convenient for updates and reviews, thus increasing the chances for consistency between implementation and technical documentation.

Automation: The DaC approach makes it easier to automate the documentation process, such as building and continuously deploying the documentation, which is a prerequisite for continuous delivery. Multiple CI/CD pipelines ensure direct feedback loops between feature teams and quality gateways, thus providing a safe environment for experimentation and learning, which is essential for software engineering and finding optimal solutions. Thousands of tests are automatically executed on every pull request update to prevent undesired behavior of the system.

Maintainability: By treating DaC, it is much easier to maintain the documentation and the source code, since they are both stored in the same version control system side-by-side. This quality attribute is tightly coupled with the ability to change, which is one of the hallmarks of good architecture. Additionally, using a single version control system simplifies the release process, since the whole package (functionality and documentation) can be bundled, tagged, and released together. This also simplifies reproducibility: one can simply check out the released package and all the relevant artifacts are present, including source code, architecture, executable specifications (acceptance tests), test results, etc.

Testability: The DaC approach is all about managing complexity and creating flexible architectures that are easy to change. In complex system environments, it is impossible to make exact predictions about the impact of even trivial changes on the overall system’s behavior. Therefore, it is necessary to have a different set of tests that can either confirm or discard our predictions about the system’s behavior after a new feature is added or a single line of code is changed. There is no agility without testability. The DaC integrates behavior-driven development (BDD) and test-driven development (TDD) methodologies, where software is designed through writing tests first and implementation second, ensuring the system’s testability at all times throughout the process on both high (BDD) and low (TDD) levels. Mid-level testability is covered with generated integration tests from the architecture model developed using Architecture as Code toolset.

Reusability: In the DaC approach, reusability is not considered a must-have under any circumstances. This property is closely related to the Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) and Single Responsibility principles. Software components are reused only when it is obvious that the reused elements will be executed in the same problem domain. However, in complex system environments, what is initially obvious can turn out to be untrue. This analysis begins with the BDD and continues through Architecture as Code until TDD. All three levels of support include (reuse element) preprocessing directives, so operational support is given by design. However, it is more important to decide when to reuse for optimal system design.

Accessibility: This is an important aspect of documentation that which DaC approach resolves twofold. First, documentation is embedded directly in the repository close to the source code and other development artifacts, which means it is accessible within the integrated development environment. This eliminates the need to leave the working environment to access the most up-to-date documentation. Second, documentation is continuously deployed to the server, ensuring it is kept up to date and accessible to everyone with the link and necessary project access rights.

Transparency is one of the three pillars of empiricism, alongside adaptation and inspection, which is ubiquitous in the DaC environment. The main infrastructures that enable transparency in DaC approach are Pull Requests and CI/CD pipelines. However, it is the content that is continuously filled in by following the DaC methodology that makes the difference. Thousands of tests are executed on all levels for each PR update and results are published on the CI server as well as in the repository, making test reports transparent from several perspectives. Transparency is also omnipresent in the ALM project structure (Fig. Jira as process guideline), which is important for MAN process group (Fig. ASPICE V-model organization). Cumulative flow diagram (Fig. Release cumulative flow chart) and various other metrics are generated from the ALM structure (Fig. Jira as process guideline), providing insights into the statuses of different user stories and release health checks.

This research was inspired by the idea of continuous and never-ending improvement (Kaizen [Ima86]) of processes and tools to produce better-quality software faster [Far21]. In DaC methodology, quality is built ground up, brick by brick (micro-V cycle by micro-V cycle), through incremental and iterative cycles. This idea was based on the philosophy of W. Edwards Deming, the father of quality, which suggested that organizations that prioritize improving quality will see a decrease in costs, whereas those that prioritize cost-cutting will inherently reduce quality and end up incurring higher costs.[DA92].

“Inspection to improve quality is too late, ineffective, costly. Quality comes not from inspection, but from the improvement of the production process.”

– W. Edwards Deming, Out of the Crisis [DCA18]

Conclusion#

We have demonstrated that the DaC approach enhances the Stability (quality) and Throughput (efficiency) of the software development project. DaC improves collaboration and accessibility of documentation, making it easier to create and maintain. Furthermore, DaC promotes the testability of the system as imperative, employing behavior-driven development (BDD) and test-driven development (TDD) methodologies.

This research has demonstrated that the DaC approach is feasible even in an area such as automotive, which is heavily dependent on consistent documentation. It has elucidated the advantageous effects of the DaC approach, and how to ensure consistent, up-to-date technical documentation throughout the project’s life-cycle management. The major conclusion from this research is that when the task of writing documentation is made attractive and easy, feature teams will regularly update it and keep it consistent. The DaC approach aims to achieve this by adjusting processes and tools to be software development-centric.

Processes and tools should be designed and selected to facilitate creativity and enjoyment during documentation crafting, just like when writing code, ideally in the same working environment. This research offered many incentives for such a conclusion on different levels and perspectives.

When writing Requirements as Code (executable specifications) using BDD methodology, such requirements become tightly coupled to the behavior of the system (not the implementation details). One side effect is full requirements coverage with acceptance tests.

Architecture as Code provides multiple opportunities for a feature team to express their creativity when designing architecture through the activity they enjoy the most – writing code. Software architecture created this way can be used as a model from which source code and integration tests can be generated. One side effect is complete interconnection coverage with generated integration tests.

Applying a test-first approach (TDD methodology), feature teams get the opportunity to design software units from the perspective of the user, thus establishing a direct feedback loop between design and customer. One side effect is full source code coverage with unit design tests.

This research has provided practical guidelines for the DaC approach. It has been demonstrated that treating all relevant documentation artifacts as source code using the same tools and working environment can have beneficial effects on consistency and software project management. However, it is important to emphasize that the DaC approach presented in this paper does not represent a final solution set in stone, but instead a solid practical process and tools framework for software project execution that embraces and facilitates the philosophy of continual, incremental, and iterative improvements, with feature teams at its focal point as organizational stem cells.

In the DaC approach, the testability of the system is considered one of the most important quality properties. Fast feedback loops embodied in CI/CD are seen as the most effective mechanisms for creating a consistent system that features teams can confidently reshape and refactor, as well as incrementally add new features and iteratively refine toward optimal solutions. This is essential for managing complexity and controlling variables during development or forensic analysis. Being always close to a safe spot when experimenting and learning is liberating. This is exactly what test coverage, CI/CD feedback loops, and version control systems provide when implemented properly. With every git commit deployed, authors get a genuine sense of continual and incremental improvement of the system. This is such a powerful psychological mechanism that encourages individuals to make small, frequent commits. The authors of the research firmly believe, based on the empirical evidence, in the described approach, and even crafted this paper [Kru23] using the same principles.

Acknowledgment#

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my colleague (and brother-in-law), Dr. Svetozar Miucin, for his invaluable guidance and support throughout this research project. I am also grateful to my colleagues Dr. Branislav Kordic and Dimitrije Stojanovic for their helpful comments and suggestions. Furthermore, I am sincerely thankful to SVP Dr. Nemanja Lukic for his selfless support, without which this research would not have been possible. Lastly, I cannot express enough appreciation to Overall PM Dr. Nenad Cetic for his invaluable contribution to my professional career (and this research).

Note

Short Reminder: This post was written and published by Dr. Momcilo Krunic, as a paper for the Elektronika ir Elektrotechnika journal. The original version can be downloaded as PDF from ResearchGate. Original sources are available on a gitlab repository under Creative Common License 4.0.

References#

Aspice guide. URL: https://knuevenermackert.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ASPICE-Guide-KM2021-01.pdf (visited on 03.02.2023).

Linux technical documentation. URL: https://www.kernel.org/doc/html/v4.10/index.html (visited on 22.01.2023).

Markdownguide. URL: https://www.markdownguide.org/ (visited on 22.01.2023).

Myst - markedly structured text - parser. URL: https://myst-parser.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (visited on 20.01.2023).

Plantuml. URL: https://plantuml.com/ (visited on 26.01.2023).

Plantuml c4. URL: plantuml-stdlib/C4-PlantUML (visited on 26.01.2023).

Sad template. URL: labsoftdev/docs-as-code/-/blob/main/templates/micro-V/Architecture/SAD-Software_Architecture_Document.md (visited on 26.01.2023).

Srd template. URL: labsoftdev/docs-as-code/-/blob/main/templates/micro-V/Requirements/SRD-Requirement_Template.md (visited on 25.01.2023).

Sphinx examples. URL: https://www.sphinx-doc.org/en/master/examples.html (visited on 23.01.2023).

Trunk based development. URL: https://trunkbaseddevelopment.com/ (visited on 23.01.2023).

Welcome - sphinx documentation. URL: https://www.sphinx-doc.org/en/master/ (visited on 20.01.2023).

Arc42. URL: https://arc42.org/ (visited on 26.01.2023).

K. Beck. Test-driven Development: By Example. Addison-Wesley signature series. Addison-Wesley, 2003. ISBN 9780321146533. URL: https://books.google.de/books?id=CUlsAQAAQBAJ.

Brooks. No silver bullet essence and accidents of software engineering. Computer, 20(4):10–19, 1987. doi:10.1109/MC.1987.1663532.

James Clear. Atomic Habits: Tiny Changes, Remarkable Results : An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones. Avery, an imprint of Penguin Random House, New York, New York, 2018, 1st edition, 2018. ISBN 9780735211292, 0735211299.

Melvin E Conway. How do committees invent. Datamation, pages 4, 1968. URL: http://www.melconway.com/Home/pdf/committees.pdf.

W.E. Deming and British Deming Association. A System of Profound Knowledge. British Deming Association, 1992. ISBN 9781873915097. URL: https://books.google.de/books?id=v-RSMwEACAAJ.

W.E. Deming, K.E. Cahill, and K.L. Allan. Out of the Crisis, reissue. MIT Press, 2018. ISBN 9780262350037. URL: https://books.google.de/books?id=PTNwDwAAQBAJ.

D. Farley. Modern Software Engineering: Doing What Works to Build Better Software Faster. ADDISON WESLEY Publishing Company Incorporated, 2021. ISBN 9780137314911. URL: https://books.google.de/books?id=ZKxHzgEACAAJ.

N. Forsgren, J. Humble, and G. Kim. Accelerate: The Science Behind DevOps : Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations. G - Reference,Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. IT Revolution, 2018. ISBN 9781942788331. URL: https://books.google.de/books?id=85XHAQAACAAJ.

S. Freeman and N. Pryce. Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests. Addison-Wesley Signature Series (Beck). Pearson Education, 2009. ISBN 9780321699763. URL: https://books.google.de/books?id=QJA3dM8Uix0C.

Jez Humble and David Farley. Continuous Delivery: Reliable Software Releases through Build, Test, and Deployment Automation. Addison-Wesley Professional, 1st edition, 2010. ISBN 0321601912.

M. Imai. Kaizen: The Key To Japan's Competitive Success. McGraw-Hill Education, 1986. ISBN 9780075543329. URL: https://books.google.de/books?id=q0rCTQlvNMoC.

Momcilo Krunic. Documentation as code in automotive system/software engineering. jan 30 2023. [Online; accessed 2023-01-30]. URL: momcilo_krunic/elektronika_ir_elektrotechnika_2023/.

G. Melnik and R. Jeffries. Introduction: tdd–the art of fearless programming. IEEE Software, 24(03):24–30, may 2007. doi:10.1109/MS.2007.75.

M. Mueller and K. Hoermann. Automotive SPICE in Practice: Surviving Interpretation and Assessment. Rocky Nook Series. Rocky Nook, 2008. ISBN 9781933952291. URL: https://books.google.de/books?id=7wcoAQAAMAAJ.

Stefan Schlichthärle, Klaus Becker, and Sebastian Sperber. A domain-specific language based architecture modeling approach for safety critical automotive software systems. In A Domain-Specific Language Based Architecture Modeling Approach for Safety Critical Automotive Software Systems. 02 2020. doi:10.4230/OASIcs.ASE.2020.2.

M. Skelton, R. Malan, and M. Pais. Team Topologies: Organizing Business and Technology Teams for Fast Flow. G - Reference,Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. IT Revolution, 2019. ISBN 9781942788812. URL: https://books.google.de/books?id=oFdRuAEACAAJ.

John Sweller, Jeroen JG Van Merrienboer, and Fred GWC Paas. Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educational psychology review, 10(3):251–296, 1998.

L. Williams, E.M. Maximilien, and M. Vouk. Test-driven development as a defect-reduction practice. In 14th International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering, 2003. ISSRE 2003., volume, 34–45. 2003. doi:10.1109/ISSRE.2003.1251029.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus